Placenames originate from the interactions between humans and places. Around the world, placenames are considered to be legacies of such interactions throughout history. Similar to historical artifacts unearthed from the ground, placenames that make space meaningful can also serve as a primary source for reconstructing the history of ancestors’ lives. Moreover, as a linguistic symbol, placenames can spread to a wider area following the movement of that language’s speakers. However, as entire language communities evolve and written languages transform, it could become difficult to thoroughly understand the meaning and origin of archaic placenames.

Toko is such a placename in the Hokkien language. Its origin is unknown, yet it is commonly used across Taiwan and even for locations and buildings in areas to where Hokkien merchants had sailed, such as Japan, Indonesia, and Thailand. Therefore, by studying the placename Toko, one can examine this name in a larger context and reconstruct the things linked together by toko in terms of both time and space.

The toko in Taiwan: The fireproof warehouse

First, let us examine the distribution of Toko as a placename in Taiwan. On the Taiwan Hōzu 臺灣堡圖, the atlas produced in the early 20th century, there are 15 locations clearly marked as Toko (expressed as either 土庫 or 塗庫 in Chinese characters). As both expressions are homonyms and synonyms in the Hokkien language, they share the same lexeme. However, what exactly does the word mean?

By examining the occurrences of both expressions of Toko in land deeds and local gazetteers, it was found that the documents with the earliest usage date back to the 18th century. At the time, the word toko still existed as a noun in the settlers’ language in Taiwan, thus it was used as a place name. Since the 19th century, however, toko seemed to have gradually faded from the Hokkien language’s lexicon, despite still being documented as a placename. As such, it was excluded from Hokkien dictionaries compiled in the latter half of the 19th century. Therefore, it is necessary to explore earlier literature to determine toko’s original meaning.

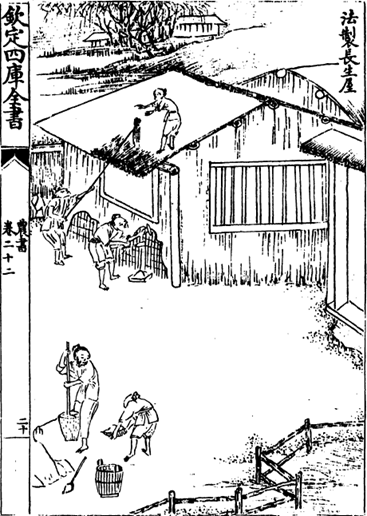

In fact, the word toko is commonly found in novels written in China during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), though authors usually assumed that the reader knew the meaning of toko and provided no further explanation. Fortunately, throughout the Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming dynasties, toko appeared to be more popular as a name for buildings in the grassroots level of society, though not among the upper class. Two historical sources outlined the advantages and construction methods of a toko. The first was The Book of Agriculture 農書, written by Wáng Zhēn 王禎 in the early 14th century. In it, the author described a toko as a building with wooden structures reinforced by adobe that was used by farmers as a fireproof warehouse. It was also known as a “house of longevity” due to its durability and resistance to fire. Wáng Zhēn believed that even if not every house in a city were built with this type of fireproof material, having at least one house built this way would obstruct fire from spreading throughout the city.

By the end of the 15th century, the Ming dynasty scholar Qiū Jùn丘濬 of Hainan Island suggested that the government should set up an archive to store official documents and books. in addition to “keeping backup copies off-site” in Beijing北京 and Nanjing 南京, e Qiū Jùn proposed fireproof archives for official documents,. The fireproof warehouse that Qiū Jùn proposed had a multi-story structure. The upper stories would house the records of previous emperors in cabinets made of copper, while the lower stories would keep the files and documents of official departments in steel cabinets for future historical reference. As described in the documents above, a toko was a type of multi-story fireproof warehouse built from fireproof materials in the country. The building was normally built further away from other wooden buildings to prevent it from being affected by fire.

If we observe the places named Toko on the atlas Taiwan Hōzu, we find that a place named Toko was often a subordinate settlement next to a major settlement. We may imagine the following scenario. After the formation of a major settlement, its residents built warehouses with fireproof materials at a certain distance. Situating the warehouses away from the settlement prevents fire from affecting the warehouse, in the event that a fire breaks out in the major settlement. The carefully chosen materials and location can provide double assurance. Such a building became a visible landmark and might become known as the place name for local residents. When a new settlement was established in the future, the place might become known as Toko.

From local to global

The tokos in Taiwan can be traced back to the fireproof warehouses used in rural China in the 14th century. In the 17th century, the Hokkien-speaking immigrants from southern Fujian Province, China, brought this construction and its name to Taiwan, and the toko became a common placename throughout the country. We also know that the Hokkien people used to sail the seas and travel to many ports in East Asia. As the Hokkien people emigrated to Southeast Asia to pursue business opportunities, they brought the toko building and its name to their new places of residence, just as their fellow immigrants did to Taiwan. Now, it has become a cultural element of modern Southeast Asia.

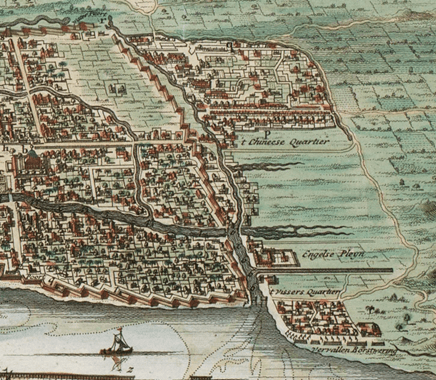

Let us first explore how the Hokkien people used the toko to describe what they saw in Southeast Asia. The early 17th-century book Study of the East and West Seas 東西洋考 by Zhāng Xiè 張燮 illustrated the Hokkien people’s world view at the time. In his description of Bantam, an important trading base on the island of Java at the time, Zhāng Xiè mentioned the tokos built by the Hu̍t-lông-ki 佛朗機 (Farang, from Arabic) people and the Âng-mn̂g-hoan 紅毛番 (the red-haired foreigner) people. Originally, Hu̍t-lông-ki was a collective name for Europeans among Middle Eastern businessmen, but here it specifically refers to the Portuguese, whereas Âng-mn̂g-hoan refers to the Dutch. At the turn of the 17th century, the Dutch repeatedly engaged in battles around Bantam with the Portuguese, who had arrived in Southeast Asia during the previous century. Their aim was to gain control of this important port. Despite allying with the British and defeating the Portuguese numerous times, and even setting up a trading post in Bantam in 1603, the Dutch finally decided to establish a permanent trading post in Kelapa, an affiliate town of Bantam. This decision was made due to the competition with the Chinese and the interference in commercial activities by the Sultan in Bantam. Kelapa developed and became Batavia. Today it is known as Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital.

In Bantam, the Chinese and the Europeans observed each other’s actions. In addition to the aforementioned Chinese records of the tokos built by the Europeans on the island of Java, the tokos built by the Chinese were also recorded by the Dutch. When Cornelis de Houtman led a Dutch fleet into East Asian waters for the first time in 1598, they saw that the Chinese had already established a commercial base in Bantam.

The Chinese built their city in a large square outside the main city. Most of them lived there, where they had bigger and better houses than those in the city (Bantam). The houses in the city were made of bamboo, while the Chinese built houses with stone on all four corners.

The stone (steen) mentioned here clearly refers to bricks. Although the Dutch did not have a word for toko, we can deduce from the building materials used and the historical sources written in Chinese during the Dutch colonial period that these Chinese-built brick houses in Bantam at the end of the 16th century were in fact tokos.

The Dutch toko: logie

The tokos established by the Europeans in Southeast Asia served several functions: accommodation, storage, and transshipment. Transshipment here refers to the mode of operation whereby precious metals, commodities, and spices brought by European merchant ships or Asian traders from all over Asia were transported back to Europe or other Asian markets when the wind direction is favorable. The most important toko for the early modern Europeans in Southeast Asia was the Kasteel van Batavia, situated in today’s Jakarta, Indonesia. It also served as a residence for the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. As the Dutch East India Company (VOC) expanded, the Dutch set up trading posts throughout East Asia. Some of these posts were witnessed by Hokkien speakers, who recorded these buildings as tokos in historical sources.

In the summer of 1680, for example, a ship from Siam (Thailand) arrived in Nagasaki, Japan. In accordance with customary practice, the Chinese ship-owner and the Siamese fiscal had to report to the authorities in Nagasaki. In the report, the word toko was used for mentions of the European trading post in Ayutthaya, the capital of Siam:

The Dutch trading post and the imperial city of Siam are only separated by a wide stream, so its location is very close to the city. The trading post occupies a square piece of land to the east of the stream, and is surrounded by a wooden fence. Inside there is only one street and a large house with three stories. The ground floor is a toko, the first floor is the captain’s residence, and the second floor is for storing small items. There are four long rooms built next to the big house for administration purposes. The buildings are luxurious and beautiful. There are only about a dozen people stationed at the Dutch trading post. The port of Siam is called Bangkok, where there is a big toko for storing fur and timber guarded by three or four Dutchmen.

Trading posts were known as logie to the Dutch. The VOC built logie in major trading bases and Taiwan was no exception. According to a mid-17th-century map depicting Kasteel Zeelandia and its surrounding areas, Tayouan (today’s Anping, Tainan City). There were two logie, a new one and an old one on this sandbank. The old one (labeled C in the picture) was a two-story building built by the Governor of Formosa, Pieter Nuyts in 1628. In a letter from Nuyts to the Governor-General in Batavia dated February 28, 1628, he mentioned that the building was designed with a storage unit on the lower story and a residence unit in the upper story. The dimensions were 150 feet long and 28 feet wide. Its design and functions were similar to the three-story toko design found in Ayutthaya. This picture illustrates that the building’s door is in the middle, with stairs connecting the entrance on the ground floor to that on the first floor. This design was similar to that of the newly built official residence to the west of the building (labeled B in the picture).

However, this toko only existed for a short period. When the Chinese pirate Lâu Hiong 劉香 attacked Tayouan in early April 1634, on the afternoon of April 9, the Dutch defenders decided to withdraw merchants, soldiers, and sailors from the trading post that Nuyts built to avoid dispersing their defensive forces and to protect their fort. This incident indicates that this building could be sacrificed if a crisis occurred. In a later aerial plan of Kasteel Zeelandia, the original location of the old trading post had become a market, and the Dutch warehouses and administrative functions in Taiwan had all been moved to the official residence just below Kasteel Zeelandia. This suggests that the old trading post built by Nuyts had been demolished at some point and that a new market had been built on the original site.

Let us look again at the report from a 1680 Siamese ship. The report from the Siamese ship that were written in Chinese were required to be translated into Japanese by interpretors of Chinese in Nagasaki. In the translated version, the toko was translated into tokura 土藏, which meant a fireproof warehouse made of clay. Such buildings were quite common in Japanese cities during the Edo period (1603-1868). As timber used to be the main building material, families might have felt the need to build separate structures to store valuables in order to prevent fire from affecting their properties. The function was exactly the same as that of the aforementioned tokos in China during the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Therefore, the translator translated it into tokura to reflect the function of the building. Interestingly, the Chinese merchants, whom the Nagasaki interpreters were responsible for receiving, were required to live in the designated settlements after 1689. The new Chinese settlements were later also known as tokos to the Chinese merchants.

The Chinese Toko of Nagasaki

In The Revised Gazetteer of Fujian Taiwan Prefecture 重修福建臺灣府志 published in 1741, there was an overview of trading between Taiwan and various East Asian countries, which presented the East Asian world at that time as through the eyes of Hokkien merchants. The article “Japan” describes the situation of Chinese businessmen visiting Nagasaki, Japan as follows:

There was a China town and a geisha street in Nagasaki. When the merchant ships arrived, the local officials brought everyone to a toko. Officials sent geishas to entertain the dignitaries and it was illegal to reject them…Nagasaki was once bewitched by Catholics from the West and everyone was converted to Catholicism. It did not take long for the emperor and the shogun to find out about the incident, and all Catholics were expelled. Consequently, Western goods and merchant ships were also banned. Offenders faced most severe punishments. The authorities also cast busts of Catholics, displayed them at the port, and ordered the Chinese to trample over them… Nagasaki favored Taiwanese goods, such as white sugar, sugarcane, and water deer fur, which were several times more expensive than other goods. Nevertheless, antiques and paintings were priceless.

The toko in Nagasaki mentioned in this text refers to the Chinese settlement where the Chinese merchants were restricted to stay when they traded in Nagasaki. Since the regulation restricting the residence of Chinese businessmen only came into effect in 1689, the circumstances described here must have been after that year.

According to the painting by the local Nagasaki artist Ishizaki Yūji 石崎融思 (1768-1846), Chinese ships were anchored in the harbor when they arrived in Nagasaki. Small boats were used to transport goods to the warehouse at Shinchi 新地 (new land). This was the place where Chinese merchants stored their goods, but it was not completed at the same time as the Chinese settlement. In 1698, a fire broke out in Nagasaki, and it spread to the tokos where good were stored along the coast. Out of the 33 warehouses in total, 18 were destroyed and the Chinese merchants suffered heavy losses. Subsequently, the Nagasaki authorities reclaimed land on the southwestern side of Dejima 出島 and constructed a warehouse isolated from the mainland. It was completed in 1702. The 1741 gazetteer was published nearly 40 years after the Shinchi warehouse began operations. Although it is not clear whether the toko in Nagasaki mentioned in the 1741 gazetteer only referred to the Shinchi warehouse or included the Chinese settlement, judging from the fact that Chinese merchants had to enter the toko when they arrived in Nagasaki, it is reasonable to assume the description of the Nagasaki toko includes the Chinese settlement.

However, the Chinese settlement did not consist of fireproof buildings. Those who provided information for the 1741 gazetteer should have observed that the buildings in the Chinese settlement in Nagasaki were built of wood, yet the term toko was still used. The reason may not be related to building materials. A possible explanation is that in the eyes of Hokkien sea merchants, toko no longer solely meant fireproof warehouses, but could also be used to refer to a building, which served as a storage unit for goods and a residence for merchants. Similar to the Dutch trading posts described by the ship owners from Siam as noted above, a building could function as storage and residence. As the Chinese settlement in Nagasaki and the Shinchi warehouse also served both purposes, the meaning of the word toko expanded from a mere fireproof warehouse to a commercial base. In fact, by the 19th century, the term toko had departed from its original meaning of fireproof warehouses and became synonymous with commercial offices and stores in Southeast Asia.

The penetration of the toko into Southeast Asian culture

As previously mentioned, Hokkien sea merchants and immigrants brought the term toko to various parts of Southeast Asia, and used the same name for similar constructions that they encountered. The term spread to China and Japan and has been recorded in Chinese historical sources through today.

The Hokkien merchants who traveled on the western and eastern routes established their strongholds in Southeast Asia earlier than the Europeans. These strongholds became powerful communities that continuously encouraged the population who lived along the Chinese coast to find opportunities in Southeast Asia. One hundred and sixty years after Zhāng Xiè was published his Study of the East and West Seas, another Hokkien sea merchant, came to the island of Java and encountered constructions that could be named tokos. He was Ong Tae-Hae 王大海 of Zhāngzhōu Prefecture, a fellow of Zhāng Xiè, and he lived in Semarang. His wife was the daughter of Tân Pà-kheng 陳豹卿, the Chinese captain of Semarang. As a local dignitary of Semarang, Tân Pà-kheng also owned a large house in Batavia known as “the Toko of Semarang.” When Chinese ships arrived in Batavia and their travelers wished to continue their journey to Semarang, they gathered at the Toko of Semarang, where they were escorted to Semarang by boat. The Toko of Semarang was also the gathering place for the brothers, relatives, or even defectors belonging to the same clan. According to Ong Tae-Hae’s witness in late-18th-century Southeast Asia, the toko was already not limited to commercial purposes. Instead, it had functions similar to associations of fellow townsmen or representative offices.

The word toko was also brought to other places in Southeast Asia by the Chinese as they actively moved around in the region. It became a commonly known term to those living in the area. The German biologist Richard Wolfgang Semon lived in Ambon for some time in the late 19th century. When he arrived in Ambon, Bouman, a Dutch merchant, hosted him and brought him to a shop owned by Tja Ke Beng, a Chinese businessman. There he was able to purchase supplies, such as wine, tin, oil, food, and soda water. A local store like this was called a toko, clearly a direct transliteration from the original Chinese term.

Conclusion: the development from local to global

With reference to historical and linguistic sources, we can reconstruct the meanings that the term toko referred to in different stages in history, as well as the functions of a toko. In Chinese, the literal meaning of toko is a fireproof warehouse for storing valuable items. Normally it was an annex to a house. The term toko had spread to Fujian by the 16th century. By the end of the century, Hokkien sea merchants used the term to refer to the warehouses they saw, in the same way as their predecessors who navigated the seas in the early Ming dynasty. Only this time, what they actually saw were trading posts set up by Europeans in Siam and on the island of Java. Perhaps because of the contact with Europeans, the semantic expansion of toko included the meaning of a commercial base. As the Hokkien people moved and spread throughout Southeast Asia, the original meaning of toko disappeared in Southeast Asia by the 19th century, leaving only the commercial base meaning.

Currently, toko means “shop” in the Indonesian language. This meaning has also been spread by Indonesians to different parts of the world, even outside Southeast Asia. In the Netherlands, toko has become synonymous with Asian stores.

Finally, let me share some recent experience to conclude our survey of toko. In February 2017, I saw an Indonesian takeout restaurant at Schiphol Airport with the easy-to-understand name “Toko to go.” Conversely, as migrant workers from Indonesia have become an indispensable work force in Taiwan, the term toko has also re-entered Taiwan, where the Hokkien dialect, Taiwanese, is spoken, and has become a common name for Indonesian stores. For example, there is a shop called Toko Indo Family in my neighborhood, where a pack of Indo Mie costs only NT$8.

This article is an English summary of my (Hung-yi Chien) peer-reviewed paper, “Toko: an Etymology of a Local Placename and its Connections to the Maritime Asia” (in Chinese, 2012).

This article is different from the Chinese article 從在地到世界的土庫 on this site. Same research, different presentations.